Unit Testing in CUBA Applications

In this guide you will learn how automated testing in a CUBA application works. In particular, this guide deals with the question of how unit tests can be executed and when it makes sense to use them over integration testing.

What we are going to build

This guide enhances the CUBA Petclinic example to show how existing features can be tested in an automated fashion via unit testing:

-

display amount of pets of a given pet type for a particular Owner

-

calculation of next regular checkup date proposals for a pet

Requirements

Your development environment requires to contain the following:

-

CUBA Studio as standalone IDE or as an IntelliJ IDEA plugin

Download and unzip the source repository for this guide, or clone it using git:

Overview

In this guide you will learn how to use the techniques of unit testing without dependencies. This approach differs from the other discussed variant of middleware integration testing (see CUBA guide: middleware integration testing), where a close-to-production test environment is created for the test to run.

In case of unit testing, the test environment is very slim because basically no runtime of the CUBA framework is provided. For giving up this convenience, unit testing allows you to more easily spin up the system under test and bring it to the proper state for exercising the test case. It also cuts out a whole lot of problems regarding test data setup and is generally executed faster by orders of magnitude.

Unit Testing

Besides the integration test environment that you learned about in the middleware integration testing guide, it is also possible to create test cases that do not spin up the Spring application context or any CUBA Platform APIs at all.

The main benefits of writing a unit test in an isolated fashion without an integration test environment are:

-

locality of the test scenario

-

test execution speed

-

easier test fixture setup

In this case, the class under test is instantiated directly via its constructor. Since Spring is not involved in managing the instantiation of the class, dependency injection is not working in this scenario. Therefore, dependencies (objects that the class under test relies upon) must be instantiated manually and passed into the class under the test directly.

In case those dependencies are CUBA APIs, they have to be mocked.

Mocking

Mocking / Stubbing is a common way in test automation that helps to emulate / control & verify certain external parts that the system under the test interacts with to isolate the SUT from its outside world as much as possible.

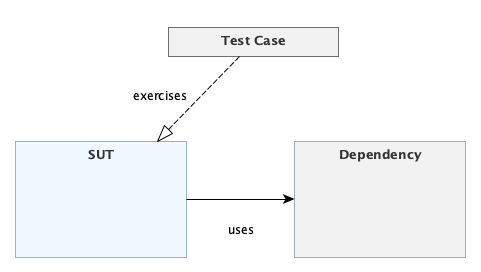

As you can see in the diagram, there is one class that acts as the system to be tested (system under test: SUT). This class uses another class responsible for helping some additional needs. This class is normally referred to as a dependency.

Stubbing or Mocking is now doing the following:

To isolate the SUT from any other dependency and to gain the test locality, the dependency is replaced with a Stub implementation. This object plays the role of a real dependency, but in the test case you control the behavior of the Stub. With that you can directly influence on the SUT behaviour, even if it has some interaction with another dependency that otherwise would be out of direct control.

Mocking Frameworks

JUnit itself does not contain Mocking capabilities. Instead dedicated Mocking frameworks allow instantiating Stub / Mock objects and control over their behavior in a JUnit test case. In this guide you will learn about Mockito, a very popular Stubbing / Mocking framework in the Java ecosystem.

An Example of Mocking

This example shows how to configure a Stub object. In this case it will replace the behavior of the TimeSource API from CUBA which allows retrieving the current timestamp. The Stub object should return yesterday. The way to define the behavior of a Stub / Mock object with Mockito is to use the Mockito API like in the following listing (3):

@ExtendWith(MockitoExtension.class) (1)

class MockingTest {

@Mock

private TimeSource timeSource; (2)

@Test

public void theBehaviorOfTheTimeSource_canBeDefined_inATestCase() {

// given:

ZonedDateTime now = ZonedDateTime.now();

ZonedDateTime yesterday = now.minusDays(1);

// and: the timeSource Mock is configured to return yesterday when now() is called

Mockito

.when(timeSource.now())

.thenReturn(yesterday); (3)

// when: the current time is retrieved from the TimeSource Interface

ZonedDateTime receivedTimestamp = timeSource.now(); (4)

// then: the received Timestamp is not now

assertThat(receivedTimestamp)

.isNotEqualTo(now);

// but: the received Timestamp is yesterday

assertThat(receivedTimestamp)

.isEqualTo(yesterday);

}

}| 1 | the MockitoExtension activates the automatic instantiation of the @Mock annotated attributes |

| 2 | the TimeSource instance is marked as a @Mock and will be instantiated via Mockito |

| 3 | the Mock behavior is defined in the test case |

| 4 | invoking the method now returns yesterday instead of the correct value |

The complete test case can be found in the example: MockingTest.java. With that behavior description in place, the one thing left is that the Stub object instance must be manually passed into the class / system under test.

Constructor Based Injection

To achieve this, one thing in the production code should be changed. CUBA and Studio by default uses Field injection. This means that if a Spring Bean A has a dependency to another Spring Bean B, a dependency is declared by creating a field in the class A of type B like this:

@Component

class SpringBeanA {

@Inject (1)

private SpringBeanB springBeanB; (2)

public double doSomething() {

int result = springBeanB.doSomeHeavyLifting(); (3)

return result / 2;

}

}| 1 | @Inject indicates Spring to instantiate a SpringBeanA instance with the correctly injected SpringBeanB instance |

| 2 | the field declaration indicates a dependency |

| 3 | the dependency can be used in the business logic of A |

In the context of unit testing, this pattern does not work quite well because the field can not be easily accessed without a corresponding method to inject the dependency. One way to create this dedicated injection method is Constructor based Injection. In this case, the class that needs a dependency defines a dedicated Constructor, annotates it with @Inject and mentions the desired dependencies as Constructor parameters.

@Component

class SpringBeanAWithConstructorInjection {

private final SpringBeanB springBeanB;

@Inject (1)

public SpringBeanAWithConstructorInjection(

SpringBeanB springBeanB (2)

) {

this.springBeanB = springBeanB; (3)

}

public double doSomething() {

int result = springBeanB.doSomeHeavyLifting(); (3)

return result / 2;

}

}| 1 | @Inject indicates Spring to call the Constructor and treat the parameters as Dependencies |

| 2 | the dependencies are defined as Constructor parameters |

| 3 | the dependency instance is manually stored as a field |

In production the code still works as before, because Spring supports both kinds of injection. In the test case we can call this constructor directly and pass it to the mocked instance configured through Mockito.

Tests for Petclinic Functionality

Next, you will see the different examples on how to use the unit test capabilities to automatically test the functionality of the Petclinic example project in a fast and isolated manner.

Pet Amount for a Particular Owner

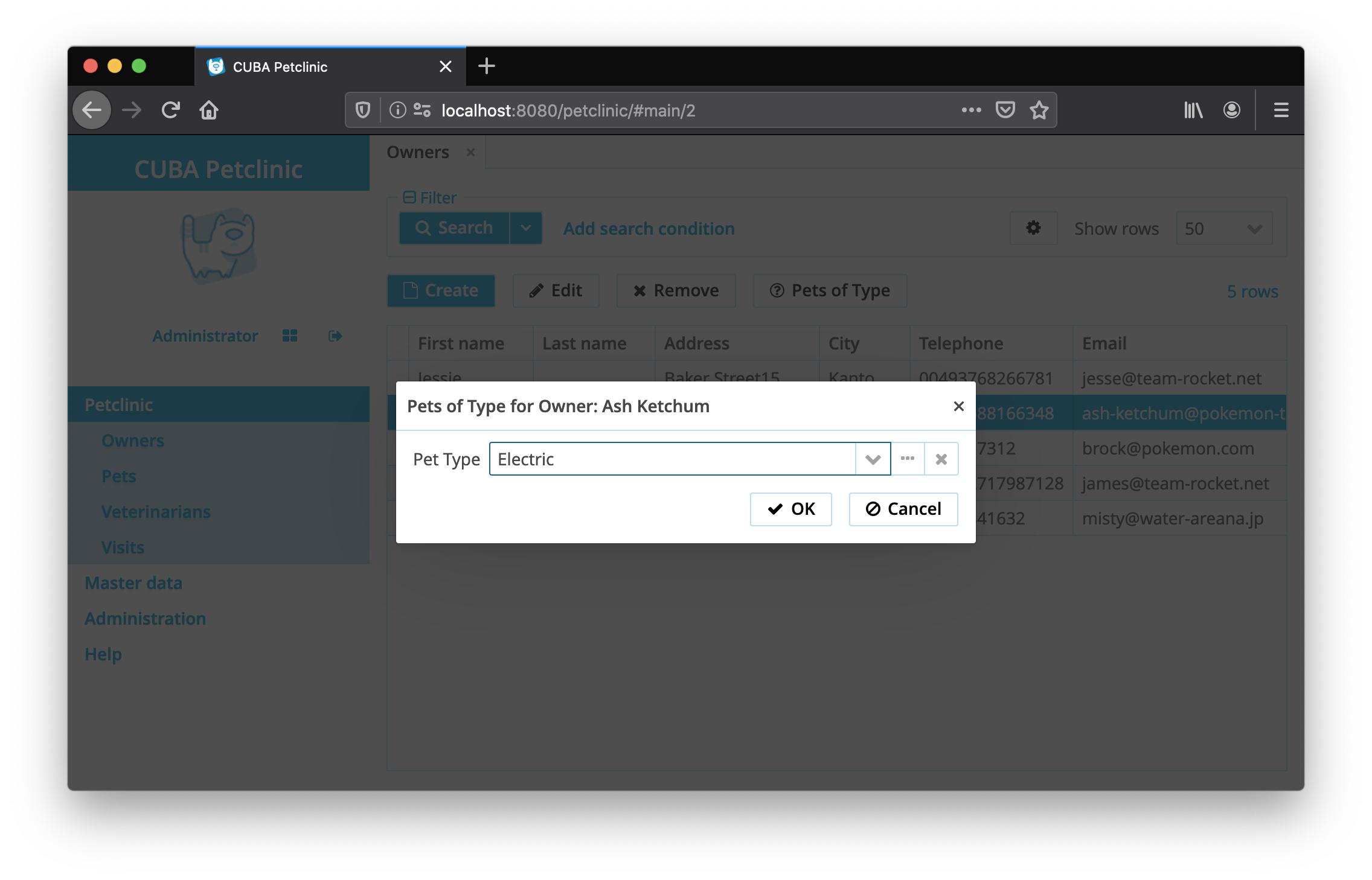

The first test case deals with the calculation of the amount of pets that are associated with an Owner for a given pet type. This feature is used in the UI to display this number when the user selects one Owner in the corresponding browse screen.

The following business rules describe the functionality:

-

If the pet type of a pet matches the asked pet type, the pet should be counted, otherwise not.

Implementation

The implementation logic is located in the Owner Entity class itself:

class Owner extends Person {

// ...

public long petsOfType(PetType petType) {

return pets.stream()

.filter(pet ->

Objects.equals(petType.getName(), pet.getType().getName())

)

.count();

}

}It uses the Java 8 Streams API to iterate over the list of pets and filter out the ones that match with the pet type name. Afterwards it counts the correctly identified pets.

Test Cases for the Happy Path

We will start with the three test cases that verify the above described business rule.

class OwnerTest {

PetclinicData data = new PetclinicData();

private PetType electric;

private Owner owner;

private PetType fire;

@BeforeEach

public void initTestData() {

electric = data.electricType();

fire = data.fireType();

owner = new Owner();

}

@Test

public void aPetWithMatchingPetType_isCounted() {

// given:

owner.pets = Arrays.asList( (1)

data.petWithType(electric)

);

// expect:

assertThat(owner.petsOfType(electric)) (2)

.isEqualTo(1);

}

@Test

public void aPetWithNonMatchingPetType_isNotCounted() {

// given:

owner.pets = Arrays.asList(

data.petWithType(electric)

);

// expect:

assertThat(owner.petsOfType(fire))

.isEqualTo(0);

}

@Test

public void twoPetsMatch_andOneNot_twoIsReturned() {

// given:

owner.pets = Arrays.asList(

data.petWithType(electric),

data.petWithType(fire),

data.petWithType(electric)

);

// expect:

assertThat(owner.petsOfType(electric))

.isEqualTo(2);

}

}| 1 | the pets are configured for the owner |

| 2 | petsOfType is executed with a particular type and the outcome is verified |

The first test case is a positive test case, which contains the simplest amount of test fixture setup possible. The second test case is of the same kind but for a negative expectation. The third test case is a combination of both test cases.

Oftentimes it is a good idea to make the test data as small and clear as possible, because it shows better the essence of the test case.

With those tests in place, we have covered all code paths that are living along the happy path.

| Happy path is a term describing the code execution path that works with valid input values and no error scenarios. |

But if we think a little bit outside of this happy path, we will find a couple of more test cases to be written.

Testing Edge Cases

When thinking of the edge cases of that method, there are multiple error scenarios to consider. Just imagine the following situation:

The LookupField in the UI does not require a pet type to be entered. If the user uses it and does not select a type and clicks OK, the passed in PetType will be null. What happens in this case in the implementation? It will produce a NullPointerException.

| Thinking about edge cases in tests is very important because it reveals bugs in the implementation that otherwise can be found only at the application runtime. |

Now, to deal with that behavior, we will create a test case that proves this hypothesis:

class OwnerTest {

// ...

@Test

public void whenAskingForNull_zeroIsReturned() {

// expect:

assertThat(owner.petsOfType(null))

.isEqualTo(0);

}

}By defining that edge case, we also defined the expected behavior of the API. In this case we defined that the return value should be zero. Running the test case shows the existence of the NullPointerException in this situation.

With this knowledge and test case that will tell us when we have reached a success state, we can adjust the implementation to behave according to our specification:

class Owner {

public long petsOfType(PetType petType) {

if (petType == null) {

return 0L;

}

return pets.stream()

.filter(pet -> Objects.equals(petType.getName(), pet.getType().getName()))

.count();

}

}Running the test case once again, we will see that the application can now deal with "invalid" inputs and react to them accordingly.

The next similar edge case is when one of the owner’s pets has no type assigned. This is possible due to the current implementation of the entity model, Pet.type is not required.

In this case, we would like to exclude those pets from counting. The following test case will show the desired behavior:

class OwnerTest {

// ...

@Test

public void petsWithoutType_areNotConsideredInTheCounting() {

// given:

Pet petWithoutType = data.petWithType(null);

// and:

owner.pets = Arrays.asList(

data.petWithType(electric),

petWithoutType

);

// expect:

assertThat(owner.petsOfType(electric))

.isEqualTo(1);

}

}Executing the test shows another NullPointerException in the implementation. The following change will make the test case pass:

class Owner {

public long petsOfType(PetType petType) {

if (petType == null) {

return 0L;

}

return pets.stream()

.filter(pet -> Objects.nonNull(pet.getType())) (1)

.filter(pet -> Objects.equals(petType.getName(), pet.getType().getName()))

.count();

}

}| 1 | pets without a type will be excluded before doing the comparison |

With that, the first example unit test is complete. As you have seen, thinking about the edge cases is just as necessary as testing the happy path. Both variants are required for a complete test coverage and a comprehensive test suite to rely on.

One additional thing to note here is that when you look at the test, it covers not the end to end feature from the UI to the business logic (and potentially the database). This is the very nature of a unit test. Instead, the normal way of tackling this issue would be to create other unit tests for the other parts in isolation as well. Oftentimes a smaller set of integration tests would also be created to verify the correct interaction of different components.

The way to write the test case first to identify a bug / develop a feature / prove a particular scenario is called Test Driven Development - TDD. With this workflow you can get a very good test coverage as well as some other benefits. In the case of fixing a bug it also gives you a clear end point where you know that you have fixed the bug.

|

Next Regular Checkup Date Proposal

The next more comprehensive example is the functionality for the Petclinic project that allows the user to retrieve the information when the next regular checkup is scheduled for a selected pet. The next regular Checkup Date is calculated based on a couple of factors. The pet type determines the interval and when the last regular checkup was.

The calculation is triggered from the UI in a dedicated Visit Editor for creating Regular Checkups: VisitCreateRegularCheckup. As part of that logic triggered by the UI, the following service method is used, which contains the business logic of the calculation:

public interface RegularCheckupService {

@Validated

LocalDate calculateNextRegularCheckupDate(

@RequiredView("pet-with-owner-and-type") Pet pet,

List<Visit> visitHistory

);

}The implementation of the Service defines two dependencies that it needs in order to perform the calculation. The dependencies are declared in the constructor so that the unit test can inject its own implementation of the dependency.

@Service(RegularCheckupService.NAME)

public class RegularCheckupServiceBean implements RegularCheckupService {

final protected TimeSource timeSource;

final protected List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> calculators;

@Inject

public RegularCheckupServiceBean(

TimeSource timeSource,

List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> calculators

) {

this.timeSource = timeSource;

this.calculators = calculators;

}

@Override

public LocalDate calculateNextRegularCheckupDate(

Pet pet,

List<Visit> visitHistory

) {

// ...

}

}The first dependency is the TimeSource API from CUBA for retrieving the current date. The second dependency is a list of RegularCheckupDateCalculator instances.

The implementation of the service does not contain the calculation logic for different pet types within the calculateNextRegularCheckupDate method. Instead it knows about possible Calculator classes. It filters out the only calculator that can calculate the next regular checkup date for the pet and delegates the calculation to it.

The API of the RegularCheckupDateCalculator looks like this:

/**

* API for Calculators that calculates a proposal date for the next regular checkup date

*/

public interface RegularCheckupDateCalculator {

/**

* defines if a calculator supports a pet instance

* @param pet the pet to calculate the checkup date for

* @return true if the calculator supports this pet, otherwise false

*/

boolean supports(Pet pet);

/**

* calculates the next regular checkup date for the pet

* @param pet the pet to calculate checkup date for

* @param visitHistory the visit history of that pet

* @param timeSource the TimeSource CUBA API

*

* @return the calculated regular checkup date

*/

LocalDate calculateRegularCheckupDate(

Pet pet,

List<Visit> visitHistory,

TimeSource timeSource

);

}It consists of two methods: supports defines if a Calculator is capable of calculating the date proposal for the given pet. In case the calculator is, the second method calculateRegularCheckupDate is invoked to perform the calculation.

There are several implementations of this interface in the implementation. Most of them implement the specific date calculation for a particular pet type.

Testing the Implementation with Mocking

In order to instantiate the SUT: RegularCheckupService, we are forced to provide both of the declared dependencies in the Constructor:

-

TimeSource -

List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator>

We will provide a Stub implementation for the TimeSource in this test case via Mockito.

For the list of the Calculators, instead of using a Mock instances, we’ll use a special test implementation. This can also be seen as a Stub, but instead of defining it on the fly via Mockito, a dedicated class ConfigurableTestCalculator is defined in the test sources. It has two static configuration options: the answers to the two API methods support and calculate.

/**

* test calculator implementation that allows to statically

* define the calculation result

*/

public class ConfigurableTestCalculator

implements RegularCheckupDateCalculator {

private final boolean supports;

private final LocalDate result;

private ConfigurableTestCalculator(

boolean supports,

LocalDate result

) {

this.supports = supports;

this.result = result;

}

// ...

/**

* creates a Calculator that will answer true

* to {@link RegularCheckupDateCalculator#supports(Pet)} for

* test case purposes and returns the provided date as a result

*/

static RegularCheckupDateCalculator supportingWithDate(LocalDate date) {

return new ConfigurableTestCalculator(true, date);

}

@Override

public boolean supports(Pet pet) {

return supports;

}

@Override

public LocalDate calculateRegularCheckupDate(

Pet pet,

List<Visit> visitHistory,

TimeSource timeSource

) {

return result;

}

}This test implementation is another form of exchanging the dependency in the test case. Using a Mocking framework or providing static test classes is more or less the same from a 10'000 feet point of view and supports the same goal.

As the unit test for the RegularCheckupService should verify the behavior in an isolated fashion, the purpose of this test is not to test the different calculators. Instead the test case is going to verify the corresponding orchestration that the service embodies.

The implementation of the calculators will be tested in dedicated unit tests for those classes.

Testing the Orchestration in RegularCheckupService

Starting with the test case for the RegularCheckupService, the following test cases cover the majority of the orchestration functionality:

-

only calculators that support the pet instance will be asked to calculate the checkup date

-

in case multiple calculators support a pet, the first one is chosen

-

in case no calculator was found, next month will be used as the proposed regular checkup date.

You can find the implementation of the test cases in the listing below.

The JUnit Annotation @DisplayName is used to better describe the test cases in the test result report. Additionally it helps to link the test case implementation to the above given test case descriptions.

|

@ExtendWith(MockitoExtension.class)

class RegularCheckupServiceTest {

//...

@Mock

private TimeSource timeSource;

private PetclinicData data = new PetclinicData(); (1)

@BeforeEach

void configureTimeSourceToReturnNowCorrectly() {

Mockito.lenient()

.when(timeSource.now())

.thenReturn(ZonedDateTime.now());

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"1. only calculators that support the pet instance " +

"will be asked to calculate the checkup date"

)

public void one_supportingCalculator_thisOneIsChosen() {

// given: first calculator does not support the pet

RegularCheckupDateCalculator threeMonthCalculator =

notSupporting(THREE_MONTHS_AGO); (2)

// and: second calculator supports the pet

RegularCheckupDateCalculator lastYearCalculator =

supportingWithDate(LAST_YEAR); (3)

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup = calculate( (4)

calculators(threeMonthCalculator, lastYearCalculator)

);

// then: the result should be the result that the calculator that was supported

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(LAST_YEAR);

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"2. in case multiple calculators support a pet," +

" the first one is chosen to calculate"

)

public void multiple_supportingCalculators_theFirstOneIsChosen() {

// given: two calculators are valid; the ONE_MONTH_AGO calculator is first

List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> calculators = calculators(

supportingWithDate(ONE_MONTHS_AGO),

notSupporting(THREE_MONTHS_AGO),

supportingWithDate(TWO_MONTHS_AGO)

);

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup = calculate(calculators);

// then: the result is the one from the first calculator

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(ONE_MONTHS_AGO);

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"3. in case no calculator was found, " +

"next month as the proposed regular checkup date will be used"

)

public void no_supportingCalculators_nextMonthWillBeReturned() {

// given: only not-supporting calculators are available for the pet

List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> onlyNotSupportingCalculators =

calculators(

notSupporting(ONE_MONTHS_AGO)

);

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup = calculate(onlyNotSupportingCalculators);

// then: the default implementation will return next month

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(NEXT_MONTH);

}

/*

* instantiates the SUT with the provided calculators as dependencies

* and executes the calculation

*/

private LocalDate calculate(

List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> calculators

) {

RegularCheckupService service = new RegularCheckupServiceBean(

timeSource,

calculators

);

return service.calculateNextRegularCheckupDate(

data.petWithType(data.waterType()),

Lists.emptyList()

);

}

// ...

}| 1 | PetclinicData acts as a Test Utility Method holder. As no DB is present in the unit test, it only creates transient objects |

| 2 | notSupporting provides a Calculator that will not support the pet (returns false for supports(Pet pet)) |

| 3 | supportingWithDate provides a Calculator that supports the pet (returns true for supports(Pet pet)) and returns the passed in Date as the result |

| 4 | calculate is the method that contains the instantiation and execution of the service |

The full source code including the helper methods and test implementation of the Calculator can be found in the example project: RegularCheckupServiceTest.java.

Testing the Calculators

As described above, the unit test for the RegularCheckupService does not include the implementations of different calculators itself. This is done on purpose, to benefit from the isolation aspects and the localization of the test scenarios. Otherwise the RegularCheckupServiceTest would contain test cases for all different calculators as well as the orchestration logic.

Splitting the test cases for the orchestration and the calculator allows us to create a comparably easy test case setup for testing one of the calculators. In this example we will take a look at the ElectricPetTypeCalculator and the corresponding test case.

For the calculator responsible for pets of type Electric, it embodies the following business rules:

-

it should only be used if the name of the pet type is

Electric, otherwise not -

the interval between two regular Checkups is one year for electric pets

-

Visits that are not regular checkups should not influence the calculation

-

in case the pet didn’t have a regular checkup at the Petclinic before, next month should be proposed

-

if the last Regular Checkup was performed longer than one year ago, next month should be proposed

ElectricPetTypeCalculator Test Cases

You can find the implementation of the different test cases that verify those business rules below. This test class also uses the PetclinicData helper for various test utility methods.

@ExtendWith(MockitoExtension.class)

class ElectricPetTypeCalculatorTest {

private PetclinicData data;

private RegularCheckupDateCalculator calculator;

private Pet electricPet;

@BeforeEach

void createTestEnvironment() {

data = new PetclinicData();

calculator = new ElectricPetTypeCalculator();

}

@BeforeEach

void createElectricPet() {

electricPet = data.petWithType(data.electricType());

}

@Nested

@DisplayName(

"1. it should only be used if the name of the pet type " +

" is 'Electric', otherwise not"

)

class Supports { (1)

@Test

public void calculator_supportsPetsWithType_Electric() {

// expect:

assertThat(calculator.supports(electricPet))

.isTrue();

}

@Test

public void calculator_doesNotSupportsPetsWithType_Water() {

// given:

Pet waterPet = data.petWithType(data.waterType());

// expect:

assertThat(calculator.supports(waterPet))

.isFalse();

}

}

@Nested

class CalculateRegularCheckupDate {

@Mock

private TimeSource timeSource;

private final LocalDate LAST_YEAR = now().minusYears(1); (2)

private final LocalDate LAST_MONTH = now().minusMonths(1);

private final LocalDate SIX_MONTHS_AGO = now().minusMonths(6);

private final LocalDate NEXT_MONTH = now().plusMonths(1);

private List<Visit> visits = new ArrayList<>();

@BeforeEach

void configureTimeSourceMockBehavior() {

Mockito.lenient()

.when(timeSource.now())

.thenReturn(ZonedDateTime.now());

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"2. the interval between two regular Checkups " +

" is one year for electric pets"

)

public void intervalIsOneYear_fromTheLatestRegularCheckup() {

// given: there are two regular checkups in the visit history of this pet

visits.add(data.regularCheckup(LAST_YEAR));

visits.add(data.regularCheckup(LAST_MONTH));

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup =

calculate(electricPet, visits); (3)

// then:

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(LAST_MONTH.plusYears(1));

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"3. Visits that are not regular checkups " +

" should not influence the calculation"

)

public void onlyRegularCheckupVisitsMatter_whenCalculatingNextRegularCheckup() {

// given: one regular checkup and one surgery

visits.add(data.regularCheckup(SIX_MONTHS_AGO));

visits.add(data.surgery(LAST_MONTH));

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup =

calculate(electricPet, visits);

// then: the date of the last checkup is used

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(SIX_MONTHS_AGO.plusYears(1));

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"4. in case the pet has not done a regular checkup " +

" at the Petclinic before, next month should be proposed"

)

public void ifThePetDidNotHavePreviousCheckups_nextMonthIsProposed() {

// given: there is no regular checkup, just a surgery

visits.add(data.surgery(LAST_MONTH));

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup =

calculate(electricPet, visits);

// then:

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(NEXT_MONTH);

}

@Test

@DisplayName(

"5. if the last Regular Checkup was performed longer than " +

" one year ago, next month should be proposed"

)

public void ifARegularCheckup_exceedsTheInterval_nextMonthIsProposed() {

// given: one regular checkup thirteen month ago

visits.add(data.regularCheckup(LAST_YEAR.minusMonths(1)));

// when:

LocalDate nextRegularCheckup =

calculate(electricPet, visits);

// then:

assertThat(nextRegularCheckup)

.isEqualTo(NEXT_MONTH);

}

private LocalDate calculate(Pet pet, List<Visit> visitHistory) {

return calculator.calculateRegularCheckupDate(

pet,

visitHistory,

timeSource

);

}

}

}| 1 | Supports describes test cases that verify the behavior of supports() method via @Nested grouping of JUnit |

| 2 | several points in time used as test fixtures and verification values are statically defined |

| 3 | calculate is executing the corresponding method of the calculator (SUT) |

The test class uses the JUnit Annotation @Nested. This allows defining groups of test cases with the same context. In this case, it is used to group them by the methods of the SUT they test: @Nested class Supports {} for the support() method to verify, @Nested class CalculateRegularCheckupDate for the calculate() method of the API.

Furthermore, the context definition is used to create certain test data as well as @BeforeEach setup methods for all the test cases defined in this context. E.g. only in the context CalculateRegularCheckupDate it is necessary to define the timeSource mock behavior.

Limitations of Unit Testing

Unit testing in an isolated fashion has some great advantages over integration testing. It spins up a different, much smaller test environment that allows a faster test run. Also, by avoiding dependencies to other classes of the application and the framework it is based upon, the test case can be much more robust and independent of a changing environment.

But this very same isolation is also the basis for the main limitation of unit tests. To achieve this level of isolation, we have to basically encode certain assumptions on the integration points. This is true for the test environment as well as the mocked dependencies. As long as those assumptions stay true, everything is fine. But once the environment changes, there is a chance that the encoded assumptions are no longer matching the reality.

Let’s take an example of a very implicit assumption on the test environment:

In the RegularCheckupService example the expressed dependency on List<RegularCheckupDateCalculator> is sufficiently working as expected in production code, only if every Calculator is a Spring bean. This means it needs to have an annotation @Component added to the class. Otherwise, it is not picked up, and therefore it will influence the overall behavior of the business logic, because e.g. now the default value (next month) will be returned.

Furthermore, as the implementation of the service implies that the order of the injected list defines which calculator to ask first, all calculators additionally need to have an @Ordered annotation in place so that the order is defined.

Both of those examples could not be tested via a unit test, as we explicitly don’t want to test the interaction between those classes and the comparably slow test container for every unit test.

Unit tests should be the primary mechanism of testing business logic. But to cover those interaction scenarios, too, it is crucial to implement integration testing. A good rule of thumb is to test those scenarios only in an integration test. So, instead of creating all those test cases again and execute them in an integration test environment, only a small subset of those test cases should be used.

In the above mentioned example a good candidate for an integration test would be the test case: multiple_supportingCalculators_theFirstOneIsChosen which verifies that the right components are injected and the correct one is used for performing the calculation.

Summary

In this guide we learned how to use unit tests to test functionality in an isolated fashion using JUnit. In the introduction you saw the differences between using plain unit tests and middleware integration tests. In particular, no external dependencies like databases are used. Furthermore, the test environment does not leverage a test container. Instead we instantiate the SUT manually.

In order to create isolated tests, sometimes you need to leverage a Mocking framework as we did in the RegularCheckupServiceTest example. Mocking is a way to control the environment & dependencies the SUT interacts with. By exchanging particular dependencies with special test implementations, the test case is capable of setting up the behavior of the dependency (and potentially use it for verification purposes as well). In the Java ecosystem, Mockito allows configuring the dependencies and their desired behavior.

We also learned that exchanging field based injection with constructor based injection production code helps to manually inject dependencies into the SUT in testing scenarios.

The benefit of using plain unit tests over integration tests is that the tests run orders of magnitudes faster. This benefit sounds like a nice-to-have feature, but in fact it allows going down a path of much more aggressive usage of automated testing. Using test driven development (TDD) as an example technique benefits very much from fast feedback cycles provided by those execution times.

Besides the benefits in the workflow of developing the test cases, we also learned about an architectural benefit: test scenario locality. Keeping the surface area of the SUT helps to spot root causes of test failures much faster.

Finally, the test fixture setup is easier to create as well, when the surface area is kept small.

Besides the benefits we also looked at the limitations of unit testing. One example was that we are not able to verify the correct usage of particular environmental behavior the code lives in. Although our unit tests perfectly show that the business rules might be correctly defined in the calculators, the question if they are using the correct Spring annotations to be picked up by the framework in the right way cannot be easily verified by unit tests.

Therefore, using unit tests should only be used in combination with a set of integration tests that cover the remaining open questions. With this combination we can be quite sure that our application is actually working as we expect.